DISCLAIMER: Billy Riggs does not speak on (or even address) the topic below in any of his public presentations, but his interests are wide and varied, so he sometimes uses this blog to express views he finds interesting or noteworthy.

THE NIGHT OF TERROR

October 7, 1969 is a date that lives in infamy among the older citizens of Quebec much as the mere mention of December 7, 1941 or September 11, 2001 elicits a visceral response in her neighbors to the south. But rather than a planned attack, the mayhem that day had erupted as organically and spontaneously as a lawn fungus. The “Night of Terror,” as it is still known among longtime residents, had been unrehearsed and uncoordinated, but it was utterly predictable. The chaos had not arrived as a bolt-out-of-the-blue like the violence that befell Pearl Harbor or the Twin Towers. Nevertheless, anyone who correctly understood human nature could have seen this coming from light-years away.

The local Montreal city police and fire departments went on a scheduled strike at 9:00 AM that fateful day, hoping for better pay and working conditions. What ensued was pure madness. By noon, the first bank had been robbed. Five more would be hit before closing time. So many storefronts were smashed that it would take forty train car loads of glass to repair the damage. More than 100 stores were looted. A dozen buildings were torched. Property damage averaged almost 1.5 million inflation-adjusted dollars per hour before the army restored order in the wee hours of October 8. By the time the sun rose on the rubble that had been less than 24 hours earlier one of Canada’s glittering jewels (watch VIDEO from the Canadian Broadcasting Company’s contemporaneous news reportage of the event), two men had been shot dead, including a provincial police corporal called in to help quell the rioting in the absence of city officers, and 20 more wounded. The dreadful episode underscores the aptness of the “thin blue line” metaphor depicting the lone bulwark protecting civilization from anarchy: a proportionately microscopic queue of blue-clad law enforcement officers.

THE NOBLE SAVAGE

The catastrophe that shut down Montreal that day should have surprised no one, but nonetheless unleashed shock and awe among those who believe that human beings are innately good. Their blank slate (tabula rasa) theory of human nature undergirds much political thinking to this very day. The term “noble savage” was first employed by 17th century author John Dryden in his play, The Conquest of Granada. Dryden’s assumption was that man in his natural state is innocent and pure, untainted by selfishness and greed.

In this view crime, war and hatred are the result of corrupting influences introduced to the individual by society, much as smallpox was carried to the Seneca, the Cree, the Blackfeet, the Mandan and the Taino tribes of America by European settlers. This romanticized view of man remains today (even dominates in some quarters) despite thousands of years of actual human history during which war has been continual and strife has been a constant. Orderly civilization (absent the iron-fisted rule of the occasional tyrant) has been the exception, not the rule, throughout human history, a relatively recent anomaly birthed predominantly in Western Europe.

Some of the supposedly-noble “savages” from faraway lands who had been hailed as proof of mankind’s innate goodness are now known to have been absolutely brutal with their own enemies. In contradiction to the dogma, crime rates generally vary inversely with the strength of law enforcement. At the global level, the reach of our nation’s enemies extends as American military power shrinks, and retreats when we expand it. To the noble-savage crowd, the withdrawal of our troops from Iraq represented the elimination of an aggravating factor – the removal of a thorn in the flesh or a grain of sand from the eye – that should have resulted in a lowering of tensions in the area. Instead, it emboldened the crazies of ISIL and intensified the fighting. This is no coincidence or anomaly.

Adherents of the blank slate view genuinely believe that crimes are committed as an angry, spiteful retaliation against a society that permits aggressive law enforcement. In their bizarre world, a profoundly good person hears that incarceration rates are high, becomes filled with righteous indignation and is driven by this injustice to grab a gun and mug an innocent person in the park. As crazy as it sounds, the presumption that the criminal was intrinsically good prior to the crime leaves no other alternative explanation, for why else would a good person turn to crime if not induced to do so by an oppressive society?

For true believers, the August 9, 1998 New York Times headline made perfect sense: “Prison Population Growing Although Crime Rate Drops.” The salient word in that title is “although.” To the blank-slate crowd (presumably including the NYT reporter), a drop in crime could not be caused by removing criminals from the streets, for that most certainly would have had incited hordes of good people to break bad and thus produce an even higher crime rate. To them, a lower crime rate merely served as proof that incarceration had been altogether unnecessary from the start: why bother locking people up when the crime rate is dropping anyway?

It reminds me of the time I was on a plane about 15 years ago. When I requested a Diet Sprite, the flight attendant looked momentarily flustered. She shook her head in wonder and said, “I just don’t get it. Why is it always the skinny ones that order the diet drinks?” Like the Tabula-Rasa folks, she had her causes and effects backwards. People don’t order diet sodas because they’re skinny; they’re skinny because they choose drinks with fewer calories. War isn’t caused by our powerful military; it is averted. Crime doesn’t occur because of aggressive law enforcement, it is reduced by it. When politics are led by religious dogmas like the Blank Slate, the result is always the opposite of what was predicted. Believe the right things, and you will tend to do the right things; hold fast to your illusions, and all your efforts will be for naught.

BELIEFS HAVE CONSEQUENCES

William Riggs

William Riggs

Leave a Comment about this Article

Recent

Articles

Video of Billy Performing the World’s Second-Best Card Trick!

Watch as Billy Riggs presents this funny routine for 1500 people in Houston in August of 2023, and does it in every show. BTW, this is the world’s best stage card trick. He’ll be happy to do the absolute world’s best card trick for you in person, but it’s too small to do for more […]

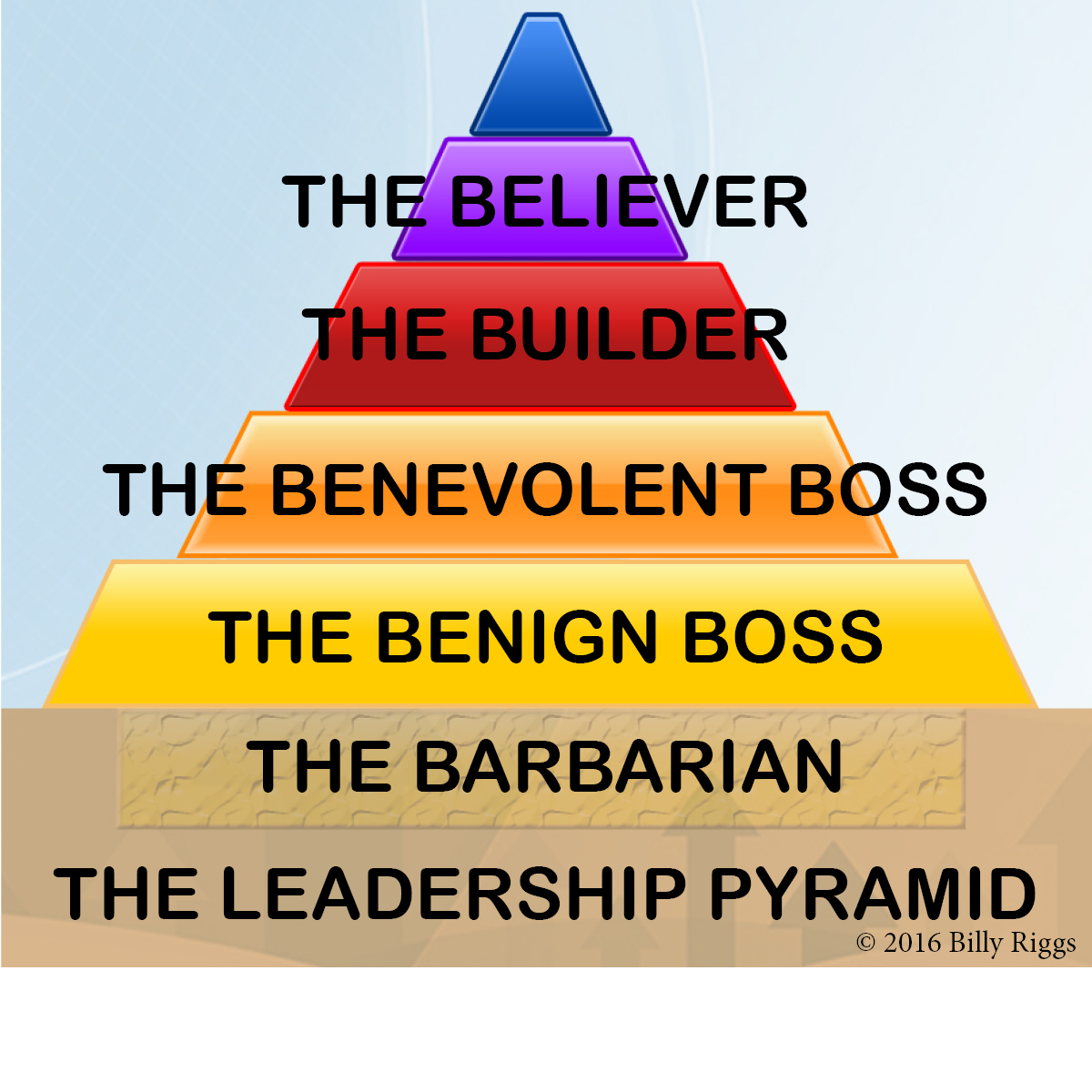

Leadership Made Simple

IT DOESN’T HAVE TO BE THIS WAY! The photo above depicts the way many people perceive the leadership process: complicated. But my diagram is much simpler: It’s a mountain. True leaders function from the mountaintop. Mere bosses languish at the bottom. As if that weren’t already simplistic enough, it’s a purely binary arrangement. You’re either […]

Be a Leader, Not Just a Boss

THE BOSS A boss and a leader are not the same things. In fact, they’re almost opposites. A boss is one who employs a series of carrots and sticks, perks and threats, promises and punishments to leverage employees into doing tasks they’d rather not do. The boss must convince staff members that their lives will […]